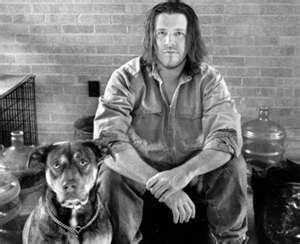

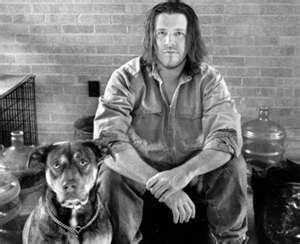

In May of 2005, David Foster Wallace, author of Infinite Jest (1996), delivered a commencement address to graduating seniors at Kenyon College. A transcription of it is still getting a lot of hits on the Internet.

In paragraph 4 of the transcription, Wallace uses what he calls a “didactic little story” to make a point about the arrogance, self-centeredness, and closed-mindedness of atheism. Here’s the story:

There are these two guys sitting together in a bar in the remote Alaskan wilderness. One of the guys is religious, the other is an atheist, and the two are arguing about the existence of God with that special intensity that comes after about the fourth beer. And the atheist says: “Look, it’s not like I don’t have actual reasons for not believing in God. It’s not like I haven’t ever experimented with the whole God and prayer thing. Just last month I got caught away from the camp in that terrible blizzard, and I was totally lost and I couldn’t see a thing, and it was 50 below, and so I tried it: I fell to my knees in the snow and cried out, ‘Oh, God, if there is a God, I’m lost in this blizzard, and I’m gonna die if you don’t help me.'” And now, in the bar, the religious guy looks at the atheist all puzzled. “Well then you must believe now,” he says, “After all, here you are, alive.” The atheist just rolls his eyes. “No, man, all that happened was a couple Eskimos came wandering by and showed me the way back to camp.”

To convey how this story struck me, an atheist, I transposed it to an entirely different religious culture, Hinduism, with Vishnu (the “protector” god) replacing the Judeo-Christian god. Here it is:

There are these two Indian chaps sitting together in a cafe enjoying chai somewhere in remote Rajasthan. One of them is a devout Hindu, and the other doesn’t profess any religion at all; his parents were non-observant members of two different faiths, and he decided as a young man that he was an atheist.

The two men start arguing about the existence of Vishnu (the Hindu “protector” god) with that special intensity that comes after about the fourth cup of chai. And the atheist says, “Look, my good friend, I actually have reasons for not believing in Vishnu. You might say I’ve ‘experimented’ with prayer to him. Just last month I got caught away from camp in the desert. I became totally lost and couldn’t see any sign of life on the horizon. The sun was beating down on my head and I was becoming dangerously dehydrated. Then I decided to try it: I fell to my knees in the sand and cried out to Vishnu, ‘Oh great and eternal protector of mankind, if you exist, then help me now, for otherwise I shall surely die!’

And now, in the cafe, the Hindu looks at the atheist all puzzled. “Well then, you must believe now,” he says, “After all, here you are, alive.” The atheist just rolls his eyes. “No, my friend,” he replies. “All that happened was that a couple of camel-drivers found me and showed me the way back to camp.”

Now, here is Wallace’s interpretation of this story, which I have edited to fit the Indian version:

Plus, there’s the whole matter of arrogance. The nonreligious guy is so totally certain in his dismissal of the possibility that the passing camel drivers had anything to do with his prayer for help. True, there are plenty of religious people who seem arrogant and certain of their own interpretations, too. They’re probably even more repulsive than atheists, at least to most of us. But religious dogmatists’ problem is exactly the same as the story’s unbeliever: blind certainty, a close-mindedness that amounts to an imprisonment so total that the prisoner doesn’t even know he’s locked up.

My first question is: Should we consider the atheist “closed-minded?” After all, in his time of greatest need, he was at least willing to “try” praying to Vishnu.

My second question: Is refusing to believe in the reality of something for which there is no evidence a sign of close-mindedness? Maybe it’s a sign of healthy-mindedness.

My third question: What could be more arrogant and self-centered than imagining that a god who ignored the prayers of six million Jews in Nazi death camps would rescue you from a mess you got yourself into?

Later, Wallace writes:

In the day-to-day trenches of adult life, there is actually no such thing as atheism. There is no such thing as not worshipping. Everybody worships. The only choice we get is what to worship.

Wallace is talking about two different things as if they were the same. One is belief and the other is worship. First you believe, and then you worship. How can you worship if you don’t believe? Is belief something we “choose” because it brings benefits like redirecting our worship away from material things to more spiritual ones?

And I don’t accept his premise that not worshipping God (any God) leads to worshipping material things. I don’t “worship” material things. I do, however, value “earthly things” like a healthy ecosystem, an end to hunger, and education and healthcare for all. I simply believe this life is all there is and we must busy ourselves making it better for everyone. Is that crass materialism?

Wallace apparently believes that there are only two choices: You worship God or you worship body, beauty, money, and power. This is just not true. What are we to make of Carl Sagan or any number of other atheists who have dedicated their lives to education, to science, or to public service?

I think Wallace has given atheists a really bad rap.